A dinghy is a critical piece of a sailing household—it’s the only way to go from your sailboat to…well, anywhere. It’s our car. Some dinghies are simple rowboats, powered only by oars; most have outboard engines. Our dinghy is a 10-foot rigid inflatable boat (rib) with a 15hp engine. When we’re not using it, we hoist it up on davits at the back of the boat where it hangs securely over the water and out of the way—it’s our garage.  Other cruisers tie their dinghy to a cleat on their boat and tow it behind when underway. At anchor or when visiting another boat, almost all of us tie our dinghies to the stern for easy access throughout the day—like parking in the driveway. Occasionally dinghies go missing—sometimes they are stolen; more often, the knot at the cleat comes undone, the painter rope that attaches to the dinghy breaks, or high tide sweeps the little crafts out to sea. Everyone we’ve met in our cruising life has a story about losing a dinghy. We’ve lost one three times (see Dinghy Walkabout when we lost our friends’ dinghy in Turks and Caicos).

Other cruisers tie their dinghy to a cleat on their boat and tow it behind when underway. At anchor or when visiting another boat, almost all of us tie our dinghies to the stern for easy access throughout the day—like parking in the driveway. Occasionally dinghies go missing—sometimes they are stolen; more often, the knot at the cleat comes undone, the painter rope that attaches to the dinghy breaks, or high tide sweeps the little crafts out to sea. Everyone we’ve met in our cruising life has a story about losing a dinghy. We’ve lost one three times (see Dinghy Walkabout when we lost our friends’ dinghy in Turks and Caicos).

On the evening before heading to the Raggeds—the southernmost Bahamian Islands where we rarely see another boat, we savored the perks of civilization when our new friends on Nomad invited us for dinner. They served an epicurean feast of red snapper in macadamia-coconut crust and entertained us with sailing sagas. We were captivated by stories of sailing from their home state of Maine to nearby Nova Scotia, a part of the planet we know little about but would love to explore. The appeal, they explained, were the people of this remote Canadian province—perfectly depicted in a tale of how they were invited to stay the night in the home of a local resident when they lost their dinghy, and consequently, the transportation back to their sailboat. Our friends had gone ashore late in the day and while getting acquainted with the couple whose homestead overlooked the anchorage, a faraway neighbor reported finding a drifting dinghy. Unbeknownst to our friends, it was their dinghy that had been swept away by the rising tide. The faraway neighbor would be happy to return the craft but, with nightfall just around the corner, they could not do so until the following day. Beds were made up, dinner served, tales told, and a friendship was born out of kindness and hospitality. Dinghy kismet.

On the evening before heading to the Raggeds—the southernmost Bahamian Islands where we rarely see another boat, we savored the perks of civilization when our new friends on Nomad invited us for dinner. They served an epicurean feast of red snapper in macadamia-coconut crust and entertained us with sailing sagas. We were captivated by stories of sailing from their home state of Maine to nearby Nova Scotia, a part of the planet we know little about but would love to explore. The appeal, they explained, were the people of this remote Canadian province—perfectly depicted in a tale of how they were invited to stay the night in the home of a local resident when they lost their dinghy, and consequently, the transportation back to their sailboat. Our friends had gone ashore late in the day and while getting acquainted with the couple whose homestead overlooked the anchorage, a faraway neighbor reported finding a drifting dinghy. Unbeknownst to our friends, it was their dinghy that had been swept away by the rising tide. The faraway neighbor would be happy to return the craft but, with nightfall just around the corner, they could not do so until the following day. Beds were made up, dinner served, tales told, and a friendship was born out of kindness and hospitality. Dinghy kismet.

We bid farewell to Nomad and returned to Gémeaux with a plan to depart the next morning before daylight so that we could transit a shallow cut at high tide. As we were climbing into bed, however, we realized we had left an electronic part on their boat. We needed the part; we couldn’t leave the anchorage without it. It was now late and all lights were off on Nomad. We would have to wait until morning to retrieve the part. Moreover, we would have to delay our departure since no respectable person would wake up a neighbor before sunrise.

We were up at first light. As soon as our friends were awake, we’d grab the part, get underway, and keep our fingers crossed that the tide would still be high enough to allow passage. We stalled as long as possible before becoming the annoying morning rooster. Allen quietly navigated the dinghy through the sleeping anchorage and sheepishly rapped on the hulls of our friend’s boat, ready to explain why he was extracting them from bed at the crack of dawn. Lights flickered on, a conversation ensued, and Allen returned to Gémeaux…flush with embarrassment. He didn’t have the part. Turns out it was in my bag all along.

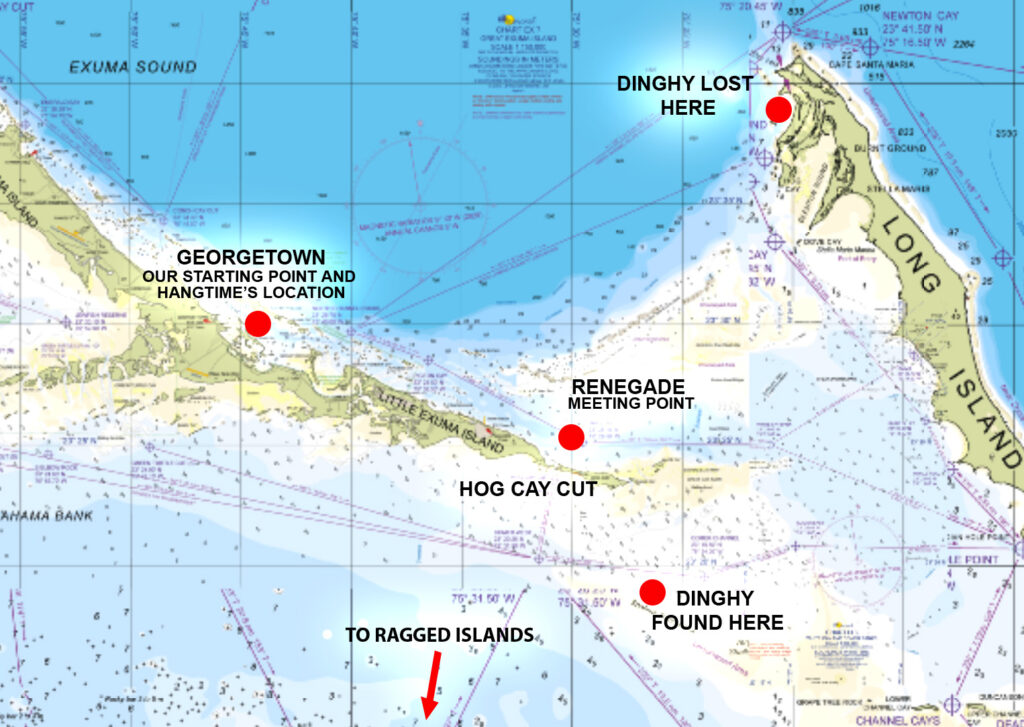

Because of our own folly, however, kismet ensued. We received a radio call from Hangtime, another cruiser in the anchorage who reported losing their dingy two days earlier while visiting Long Island, about 30 miles from our present position in George Town. Their family had anchored in Calabash Bay at the northern end of the island and it wasn’t until the end of a fun day playing in the water that they noticed the dinghy was no longer tied to their boat. Given the wind direction and current, Hangtime estimated the dinghy would be drifting south. On this early morning, they noticed us leaving the anchorage in a southbound direction and asked if we could keep an eye out for the lost dinghy. Had we left in the dark as planned, Hangtime wouldn’t have seen us departing the anchorage. We would never have known to keep a sharp lookout for a missing dinghy in our path.

Two hours past high tide, we reached Hog Cay Cut between the two islands and cleared the shallow waters without incident. We celebrated our good luck, put up the sails, and set a southbound course for the Ragged Islands. Not far behind us, we heard two motor boats on the radio debating a strategy for entering the tricky cut and then continuing on to Long Island—the southern tip, but the same island, nonetheless, from where the missing dinghy had escaped. In the spirit of spreading the word as far as we could, we radioed to the boats and asked them to keep an eye out for a drifting dinghy. We realized that more than 40 hours had now passed since the dinghy began its solo voyage. We were also six miles from shore, seas were choppy, the glare of the morning sun was bright, and honestly, it would be a small miracle to actually find the needle in this haystack of an ocean. But guess what?

Less than 30 minutes after our radio call to the two boats, we heard one ask the other in a thick southern drawl, Hey y’all, what was that sailboat called that was looking for the dinghy? I think I see something. What!!?? Break Break Gémeaux!! We interrupted the call and immediately made a 90-degree turn, abandoning our southbound sailing and becoming a dinghy rescue boat. Sailing directly into the sun now, we could just barely make out something on the horizon as we squinted through the binoculars.

Less than 30 minutes after our radio call to the two boats, we heard one ask the other in a thick southern drawl, Hey y’all, what was that sailboat called that was looking for the dinghy? I think I see something. What!!?? Break Break Gémeaux!! We interrupted the call and immediately made a 90-degree turn, abandoning our southbound sailing and becoming a dinghy rescue boat. Sailing directly into the sun now, we could just barely make out something on the horizon as we squinted through the binoculars.

This lucky little craft had traveled 30 miles almost due south without running into any islands or sharp iron shore rock, and was just bobbing along in the middle of Comers Chanel. Had we transited the cut two hours earlier as planned, we wouldn’t have crossed paths with the two motor boats. They might have missed spotting the dinghy altogether and the little boat that could would have been well on its way to Cuba. Dinghy kismet.

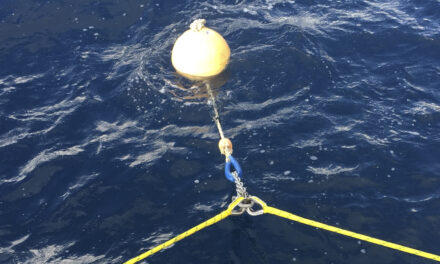

As we closed in on the dinghy, we tried to formulate a plan for what to do after we made the recovery. We were headed south and still had many more miles to make landfall before dark. Hangtime was more than two hours in the opposite direction. Moreover, the cut was now certainly too shallow for Gémeaux to pass through. Even if we abandoned our southbound plans to bring the dinghy closer to Hangtime, we couldn’t get through for another 12 hours when the tide changed again. To complicate matters, we were on the cusp of cell service with only an email address for Hangtime.  We sent emails and messages through social media and tried to contact other friends in the anchorage. We even made a general VHF radio hail for any boat in the George Town anchorage, but nothing heard. We were just too far away. We kept our thinking caps on as we approached the dinghy and tied a line to it…using a very secure knot! Once we were safely connected, we started the one-hour trek back towards the cut, frequently looking back to ensure the dinghy remained in tow. Perhaps by the time we reached cell service again and connected with Hangtime, they would meet us halfway. The thought of leaving the dinghy on a beach for them to retrieve at their convenience did occur to us, but that seemed a considerable tempt of bad dinghy fate after all this good fortune. And just like that, another stroke of kismet struck.

We sent emails and messages through social media and tried to contact other friends in the anchorage. We even made a general VHF radio hail for any boat in the George Town anchorage, but nothing heard. We were just too far away. We kept our thinking caps on as we approached the dinghy and tied a line to it…using a very secure knot! Once we were safely connected, we started the one-hour trek back towards the cut, frequently looking back to ensure the dinghy remained in tow. Perhaps by the time we reached cell service again and connected with Hangtime, they would meet us halfway. The thought of leaving the dinghy on a beach for them to retrieve at their convenience did occur to us, but that seemed a considerable tempt of bad dinghy fate after all this good fortune. And just like that, another stroke of kismet struck.

As I sat on the highest point of Gémeaux begging for a beam of internet, Allen noticed a vessel on the chart plotter that was moving north just on the other side of Hog Cay. The boat finally appeared on AIS as s/v Renegade. Allen hailed them, explained the situation, and asked if they could help. They agreed and we added another good Samaritan to the mix. We settled on a plan to anchor Gémeaux on this side of Hog Cay Cut and then tow our dinghy with Hangtime’s larger dinghy through the cut where Renegade would meet us on the other side and take over the towing service. A bar of internet service appeared and we finally got a phone call from the elated Hangtime crowd.

We anchored a mile south of the cut, deployed our dinghy, rearranged the tow lines, and sent Allen off for the transfer. Renegade was waiting on just the other side of the cut, where Allen handed off the legendary dinghy. They continued their northbound journey for the George Town anchorage, where we imagined they’d be greeted with great pageantry. Allen celebrated his own fame as he made a record third passage in a single morning through Hog Cay Cut.

We considered abandoning our sailing life and moving to Las Vegas given our string of good luck. Instead, we settled for a very good story. We pulled up anchor, put up the sails, and resumed our southern course after an exciting 3-1/2-hour interruption. We made landfall at dusk and settled in on Gémeaux’s rooftop to watch the stars and to marvel at the adventure of our day. And we made a toast—Here’s to dinghy kismet… and to good knots.

Wow the stories get better and better every year! Love this!

I see what you did there…😎 Always an adventure and love hearing about them!

2022 should be fun !

Great kismet stories! As much as we’d love to see you in Vegas, we don’t recommend it. Safe sailing and keep the stories coming.

What a great story!!

This is community. It truly takes a village. Reminded of a song…”I’ll get by with a little help from my friends.”

Love this story of good fortune and good people!