When we were planning our long passage to the Azores and Europe, I knew that weather would be one of the most critical parts of the trip. In preparation, I signed up for a 4-day marine weather class ASA119, taught by Lisa Batchelor Frailey of Kinetic Sailing. I had taken the class the previous year but decided a refresher would be a good idea. Lisa’s class teaches why weather happens, which gives a lot more insight than just looking at predicted wind speeds. I also learned how to get more information than is available from the standard tools like Windy and PredictWind. One example was learning how to use pilot charts, compilations of many years of data, in order to predict weather at a given time and place.

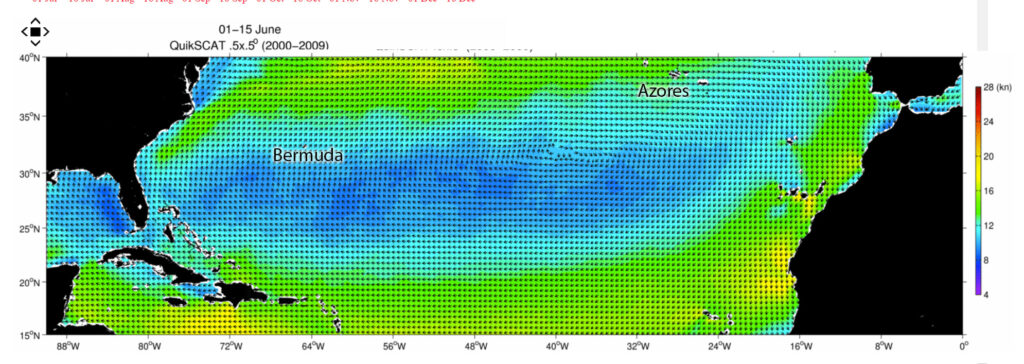

Here’s the polar chart for June 1-15 across the Atlantic. It shows an area of light winds (blue) eastward from Bermuda and stronger winds (green) northward. The data was collected from satellites over a period of 10 years and is very helpful to plan expectations for the average year. It can be viewed at http://cioss.ceoas.oregonstate.edu/cogow/index.html.

Here’s the polar chart for June 1-15 across the Atlantic. It shows an area of light winds (blue) eastward from Bermuda and stronger winds (green) northward. The data was collected from satellites over a period of 10 years and is very helpful to plan expectations for the average year. It can be viewed at http://cioss.ceoas.oregonstate.edu/cogow/index.html.

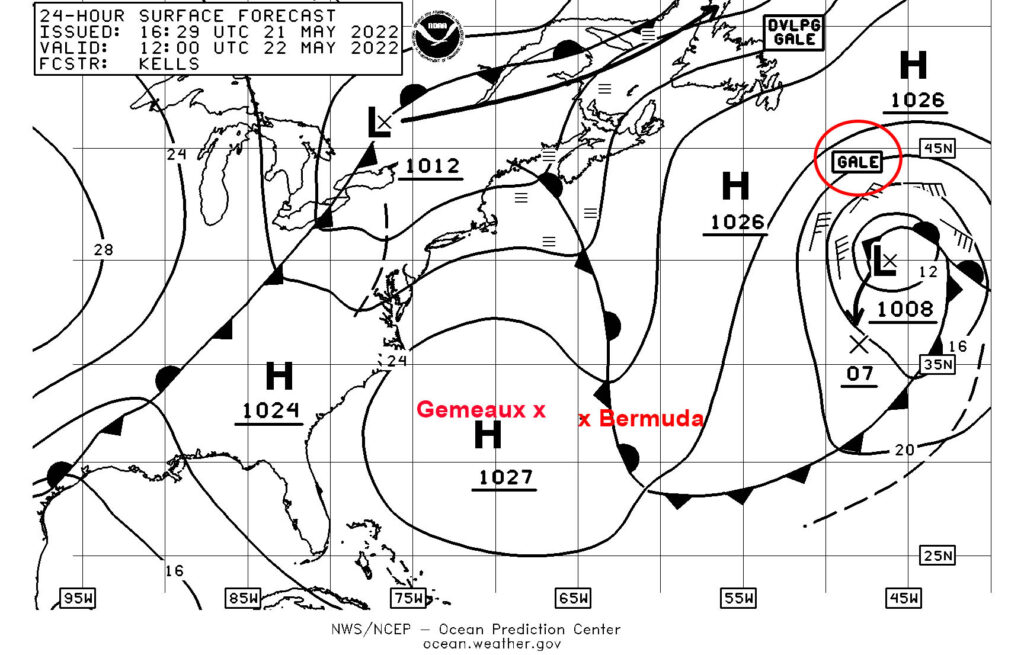

Unfortunately, we didn’t have an average year. Normally, weather fronts decrease in strength and numbers in the spring and are not much of a factor by June. In 2022, there seemed to be a steady march of fronts crossing the northern Atlantic in late spring. In Lisa’s class, she put a lot of emphasis on surface analysis charts available from NOAA. Here’s a chart from late May during our passage from Florida to Bermuda.

The surface chart shows a strong low-pressure system with gale force winds (greater than 35K) east of Bermuda on the route to the Azores. It also shows another cold front swinging across the East Coast of the US, which will later enter the Atlantic. Finally, there’s a strong high pressure between Florida and Bermuda, which accounted for the weak winds during that portion of our passage. Each day, while we were offshore, I would download the current surface chart and the predicted surface conditions for the next 48 hours to see what weather features might affect us.

To decide when to depart and what route to take, we relied heavily on the longer (10-15 day) weather models of surface winds. There are two major models, the American GFS and the European ECMWF models. These models are updated every 12 hours and forecast surface winds, winds aloft, rain, clouds and temperatures. Many companies, like Windy and PredictWind, use these models to produce user- friendly diagrams of the wind. Like many boats, we use PredictWind to display the output of the models. In her class, Lisa expanded our tool set by introducing LuckGrib, which is a very slick program to also view the output of the models. The ability to save results from the models allows users to look back at past runs of the models to see how the forecast is evolving.

In addition to just viewing the models, PredictWind and LuckGrib have the ability to suggest routing for your boat. The programs take the weather models and information about the performance of your boat in various wind conditions to determine the best route to your destination. These programs magically provide a detailed route for your trip with precise weather along the entire route. Alas, if only it was this easy and the results were that reliable. Although the information is useful as a starting point for passage planning, in many cases the results are contaminated by inaccurate forecasts and/or boat performance.

A good example of this was on our route from Florida to Bermuda. The routing software’s magical answer was to go direct to Bermuda. There was no wind on the route so it would require 6 days of motoring, but that was the fastest way to get there. Unfortunately, Gemeaux doesn’t have the fuel capacity to motor 1000 miles and with a long-range outlook of a persistent lack of wind, we would have been stuck on that route for days if we followed only the recommendation from the routing programs.

Our solution instead was to use the strong northward current of the Gulf Stream to take us above the area of high pressure where we could find a couple of days of wind to give us the necessary range to make Bermuda. By forcing the routing programs to use a northern route, they correctly forecasted we could cut our motoring time in half and only add 12 hours to passage time. Great final answer.

In addition to software and models, we hired several companies to provide expert advice. These companies employ meteorologists who evaluate the same inputs but use their experience to select the best route and provide predicted weather. We have long relied on Chris Parker of Marine Weather Center for his guidance in the Caribbean and East Coast but decided to add two more players for this passage. The new companies were Commander’s Weather and Weather Routers International.

It’s tempting to just accept the advice of a router and move on; however, that would have been a poor choice several times on this journey. On our passage from Florida to Bermuda, for example, two of the routers (like the routing software) recommended a direct route to Bermuda, even when we told them our fuel range and asked them to consider a northern route using the Gulf Stream. I’m convinced our trip to Bermuda would have taken much longer if we had followed their advice. While the router’s advice should be strongly considered, it also must be factored with the other available information.

We constantly update weather information during our passages. In the past, our communication tool has been an Iridium Go, which is reliable and not terribly expensive, but performance is very slow. For this passage, we added a new Iridium product, the Bluesky 6100, which is nearly 100x faster. The only downside is it’s capped at 25Mbyte/month, at which point they start charging an arm and a leg for data. As it turned out, we easily stayed under that limit for accessing just email and weather information.

Our passage days seemed to revolve around when the Euro weather model would be updated at 8AM and 8PM UTC for both LuckGrib and PredictWind. Two times each day, we would download new updates and run new routing analyses using our latest position. Then, we’d have a lot of discussion about the new data and decide if and how we were going to change our route or plans.

So those are the tools and resources we used. How did it all work out?

Our original target departure date for the Florida to Bermuda passage was around May 10th. As that day approached, a front was predicted to exit the US East Coast and the low pressure associated with it became “cut off” from the upper-level winds leaving it to linger just off the coast and then drift southward instead of moving to the northeast as a typical front. Indeed, that LO drifted south to the Bahamas bringing lots of squally weather and then lifted back north crossing our potential path a second time. We delayed our departure until May 16th when the LO had dissipated and had been replaced by an area of high pressure. The models suggested we would have some wind for sailing going due north in the Gulf Stream, which is just what we had. For the leg north, we had a day of motoring and a day of sailing. By May 18th, we completed our north leg and turned east for Bermuda. Our long-range plan expected to have some sailing and some motoring, which again turned out to pretty accurate. We had one surprising night when the wind was predicted to be mild at about 15K, but as the night wore on, the wind built into the mid-20s gusting to 30K. That lead to an unpleasant midnight reefing session in steep and choppy seas. Fortunately, things calmed down by morning. We arrived in Bermuda almost exactly 7 days after departure, having motored 3 days and sailed 4 days. We had plenty of fuel in reserve upon arrival.

Our next leg of the journey was much more complicated. Our target departure date was June 2nd. Nearly a week before departure, the GFS model showed a tropical disturbance coming near Bermuda around that date. Our weather guru, Chris Parker, dismissed it as “convective feedback” in the model. But, there was a hurricane brewing in the Pacific that looked like it might cross Mexico and enter the Caribbean so there was some basis for the prediction. As we neared the departure date, the GFS model did indeed drop the storm, but the Euro model picked it up, but closer to the US East Coast. The model showed the closest approach on June 6th, five full days after our departure when, by then, we would expect to be nearly 750 miles east of Bermuda. We studied the historical tropical storm tracks for the month of June and only one storm had tracked east of Bermuda in our potential path. Another favorable factor was consistent south wind along a track eastward from Bermuda, which would keep us well south of the potential tropical storm as it curved northeast after Bermuda. Finally, there was a ridge of high pressure further south that we felt could be used to escape to if needed. While it seemed a little nuts to head into the Atlantic with a tropical storm brewing, all the factors seemed to indicate it would have little effect on us. Our weather routers pretty much agreed, but one of the three suggested to wait two days before leaving. We dismissed this because that would reduce the distance to any potential storm by several hundred miles.

So how did that all work out? The storm moved faster than predicted, was stronger than predicted, and traveled more easterly than predicted. Bermuda pretty much took a direct hit from Alex on June 6th. Our 1000-mile cushion instead was only 500 miles and we caught the edge of Alex’s wind. My plan of moving south was good in theory, but it failed to consider the wind was coming from the south, so that made it difficult getting further south, especially as winds increased. We did manage to move 150 miles south of Bermuda by the time Alex passed, which did help. As Alex passed, we had winds in the upper 20s gusting to nearly gale force but they only lasted 12 hours. Prior to Alex’s arrival, one weather router recommended taking a northernly course to avoid potential calms later in the trip. We quickly dismissed that suggestion, opting to deal with the storm first and cope with no wind later.

So how did that all work out? The storm moved faster than predicted, was stronger than predicted, and traveled more easterly than predicted. Bermuda pretty much took a direct hit from Alex on June 6th. Our 1000-mile cushion instead was only 500 miles and we caught the edge of Alex’s wind. My plan of moving south was good in theory, but it failed to consider the wind was coming from the south, so that made it difficult getting further south, especially as winds increased. We did manage to move 150 miles south of Bermuda by the time Alex passed, which did help. As Alex passed, we had winds in the upper 20s gusting to nearly gale force but they only lasted 12 hours. Prior to Alex’s arrival, one weather router recommended taking a northernly course to avoid potential calms later in the trip. We quickly dismissed that suggestion, opting to deal with the storm first and cope with no wind later.

After Alex passed us, we now could focus on how to complete the next 1000 miles into the Azores. We were hundreds of miles south of the normal track for boats headed to the Azores and the routing advice was all over the map. We had suggestions to head due north, due east, or to continue on a direct path to the Azores. All these divergent suggestions were due to rapidly evolving weather forecasts as we neared the Azores seven days later. Every 12 hours, we would get a markedly different forecast for the upcoming winds and the routing suggestions reflected which model that router had decided to focus on.

We decided to head mostly straight to the Azores until the forecasts became a little more consistent. That was a good decision as we had several days of good wind before hitting a day-long calm, which we had to motor through. At the end of the calm, winds were strong from the north to the east of our position, so we finally turned north in search of favorable winds. The first day headed north we were closed hauled and when the winds increased late in the day, it was an uncomfortable ride. By morning, the direction had become more westerly and smoothed out. We had been expecting to cross a windless ridge, but it pretty much dissipated giving us a nice ride for the last two days into Horta.

Weather certainly was the most important factor in our passage. We had access to lots of resources to get information but then had to sort all that information to decide which to believe and which to ignore as we considered our course. In general Chris Parker did a great job in providing routing advice. Commander’s forecasts were also good, but they provided less guidance. In general, we found the European model to be more accurate than the GFS, but in both cases the actual wind was usually stronger than forecasted.

Wow Allen, it sounds like you were busy with all these weather challenges. Would you use all these resources again for your next trip, or did you feel overwhelmed with all that data?

Ted… Great to hear from you as we follow in your footsteps to the Med. Having three routers was a lot, but I would probably do two again. It was really interesting to see their different perspectives. In the end, we did what we felt was the best plan, but I think in all cases it was one that at least one router agreed on. 🙂

You got me looking at LuckGrib again. The biggest issue that I have had with it is that it did not include ECMWF model prediction data. Is this still the case? They have some confusing information on their website. In one place, they talk about passing on free weather data at no cost (however ECMWF is not free), and then in another section they talk about having weather data from ECMWF available for download. However, the ECMWF data that they reference are current observations (ie. wind speed, pressure, …) but not the prediction model. So, is the ECMWF prediction model available in LuckGrib or not?

Not sure what deal they did, but you can get some of the Euro model parameters; Wind, Pressure, Total Rain for 10 days. LuckGrib best I can tell is written by one guy, Craig. He is super responsive to email. The downside is it only runs on Apple products. To do routing, you really will want something bigger than a phone. I used an IPad which was great. Luckgrib doesn’t charge for access, just the program. To buy the full suite is like $150.