There’s no better place to understand weather than in Antarctica. In 2009, we had the amazing honor to retrace the steps of famed explorer, Ernest Shackleton. Adorned with snowshoes, backpacks, and foul-weather gear for all types of foul, we snowshoed 25 miles over three days across South Georgia Island. On our first night, pelting ice blew sideways and 40mph winds threatened to blow us off the mountain. It was one of the best nights of my life. It was the moment I realized how much I love intense weather.

To be clear, I love a good storm when I’m protected. It doesn’t need to be a bomb shelter—a good tent will do. Once nestled in my sleeping bag cocoon in the safety of our tent, that Antarctic storm drowned out all the worries and noises from civilization—all the to-do lists, all the hatred from an ex-husband, all the worry of breast cancer returning. A front row seat at Mother Nature’s magnificent show clears your head and fills your heart with gratitude—mostly for your shelter. Perhaps it’s the gratitude that opens your senses to really hear how the wind whistles and howls and how ice pellets beat on your roof like a machine gun.

Being on a boat during a storm is extraordinary. Let me rephrase that—being on a boat that is anchored is extraordinary. While at sea, far far from land, I prefer to avoid the wrath of Mother Nature. From the safety of anchor, however, you are perfectly positioned to see the wicked dark storm clouds roll in from the horizon. Sails and straps begin flapping as the wind picks up. A dark band of ripples in the water serve as a gauge to know exactly when the storm will place you in its epicenter. Often, only a few minutes of sprinkles give any warning of precipitation. In an instant, rain is pounding so hard and so fast that the world around you is just a blur. You are in your own little rainstorm and it is glorious.

And then lightning strikes. While certainly a beautiful addition to this performance, I’m pretty sure it’s better to watch the strikes on the horizon. There’s been a lot of discussion among our crew about how lightening affects a boat. Our captain reports that 90% of lightning strikes are from cloud to cloud; only a small number of strikes actually go from cloud to ground. Hmmm…that might need some fact checking. Let’s just assume we’re at risk; after all, we have a 70-foot lightening rod begging to be the center of attention. The captain further explains that there’s a wire that runs from the base of the mast to a metal block on the bottom of the boat to ground the lightning bolt. Furthermore, while plain water isn’t very conductive, if you add a little salt, conductivity increases dramatically. So, it’s a good thing we’re in the ocean and not in Lake Tahoe.

And then lightning strikes. While certainly a beautiful addition to this performance, I’m pretty sure it’s better to watch the strikes on the horizon. There’s been a lot of discussion among our crew about how lightening affects a boat. Our captain reports that 90% of lightning strikes are from cloud to cloud; only a small number of strikes actually go from cloud to ground. Hmmm…that might need some fact checking. Let’s just assume we’re at risk; after all, we have a 70-foot lightening rod begging to be the center of attention. The captain further explains that there’s a wire that runs from the base of the mast to a metal block on the bottom of the boat to ground the lightning bolt. Furthermore, while plain water isn’t very conductive, if you add a little salt, conductivity increases dramatically. So, it’s a good thing we’re in the ocean and not in Lake Tahoe.

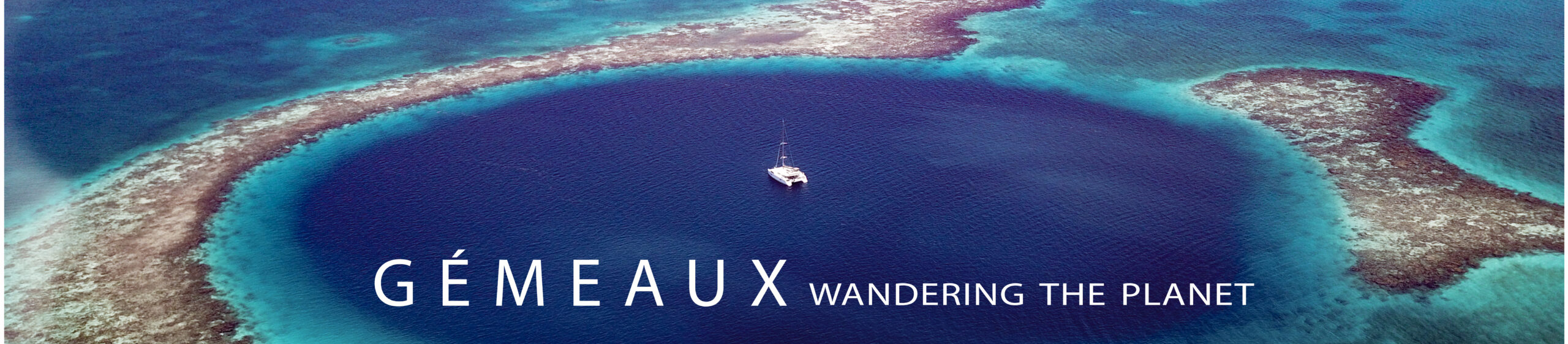

While I feel better that lightning is not going to kill me, it does kill most everything on a boat. And that’s exactly what happened to poor Gémeaux. We weren’t even on the boat and in fact, the boat wasn’t even in the water. Gémeaux was perched on 6-foot iron jacks in the Port Annapolis boat yard.  On the hard, as they say, which I think means hard repairs that are hard on your wallet. For a month, Gémeaux was poked and prodded to fix steering, replace plumbing, etc, etc—the typical endless list of boat repairs. And boy was it endless. We had given that damn mouse a cookie and we were spiraling down its little hole, one step forward and two steps back. We changed the plumbing in the heads and then discovered the through holes leak. We fixed the steering and then the inverter stopped working. We installed a new autopilot and suddenly the AIS was on the blitz. And then, we realized that most of the electronics seemed mostly dead, as Billy Crystal would say to the Princess Bride.

On the hard, as they say, which I think means hard repairs that are hard on your wallet. For a month, Gémeaux was poked and prodded to fix steering, replace plumbing, etc, etc—the typical endless list of boat repairs. And boy was it endless. We had given that damn mouse a cookie and we were spiraling down its little hole, one step forward and two steps back. We changed the plumbing in the heads and then discovered the through holes leak. We fixed the steering and then the inverter stopped working. We installed a new autopilot and suddenly the AIS was on the blitz. And then, we realized that most of the electronics seemed mostly dead, as Billy Crystal would say to the Princess Bride.

It wasn’t until a worker relayed a story of a boat in their boatyard getting struck by lightning that the puzzle started to come together. Typically when a boat is struck, there’s some visible evidence like a charred mast or a missing antenna. Gémeaux had no visible wounds and all parts were accounted for. However, she did have the misfortune of being parked adjacent to the lightning victim so suffering lightning damage was entirely possible. It seemed the only explanation.

“Replace ALL the electronics,” fellow boat owners recommended, “It might function today but it’s definitely been damaged and you’ll discover it down the road, er out at sea at a most inconvenient time.” And with that advice, we filed an insurance claim and set about replacing all the electronics. The only upside? How often do you get hit by lightning? We’re more likely to be eaten by a shark…maybe not a good analogy.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up to receive email notifications of future posts!