It’s 80 miles long and only four miles across at its widest point. It’s home to the second deepest blue hole in the world and some of the oldest churches in the country. You can get married here but you’ll need proof of spinstership! to take your vows. That’s the short of it. Want to hear the long story?

South of Miami and closer to Cuba than to the US sits one of the most scenic islands of The Bahamas. The Tropic of Cancer splits the island, putting the sun directly overhead secluded stretches of pink sand beaches on the Summer Solstice. Long Island is one of southern-most Out or Family Islands in The Bahamas—away from the glitz of Nassau. Sparsely populated with only 3000 residents, its lineage dates back to the 1700s and even further to 1492 when Christopher Columbus made landfall here.

South of Miami and closer to Cuba than to the US sits one of the most scenic islands of The Bahamas. The Tropic of Cancer splits the island, putting the sun directly overhead secluded stretches of pink sand beaches on the Summer Solstice. Long Island is one of southern-most Out or Family Islands in The Bahamas—away from the glitz of Nassau. Sparsely populated with only 3000 residents, its lineage dates back to the 1700s and even further to 1492 when Christopher Columbus made landfall here.

On this fall day, we arrived at Flying Fish Marina in the island’s capital of Clarence Town and hub for the sport fishing crowd. You can find the marina by locating the twin whitewashed church steeples on the overlooking hillside—that is two churches each with two steeples. Specifically, St. Paul’s Anglican Church and St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s Church. Both churches were designed by Jerome Hawes, originally an Anglican priest but then converted to Catholicism. Still with me?

Like every marina so far this year in The Bahamas, we had the place nearly to ourselves. We entered our slip at low tide in just a few feet of water amid warning signs of shark sightings. Each time the sporty fishermen bring in their catch, they bring in a swarm of sharks for a feeding frenzy of unwanted fish pieces. While this provided us hours of entertainment and a lesson on identifying different types of sharks, we gave Zemi a stern parental lecture that this would be a very bad time for a swimming lesson.

We settled into marina life, which meant access to luxuries like a laundry room, restaurant, WiFi, fuel, and of course, ice cream. It also came with access to a rental car, which meant we could buy groceries and see the sights on land. We gobbled down Klondike bars and gave Gémeaux a bath—fresh water also being a luxury (although at .30/gallon, the bath was quick). We dusted off our face masks and headed out to explore civilization.

Driving in The Bahamas is always a challenge to the brain. No matter how hard you concentrate on staying left, a life of driving in the US forces you to expect oncoming traffic from the other side. Thankfully, the captain transitions easily from the helm to steering wheel and we made our way around the island without incident. Our main objective was to provision aka get groceries aka find pineapple for the captain. The guidebooks told us there were three markets on this south side of the island. The books also said there was a giant hole on the way.

Driving in The Bahamas is always a challenge to the brain. No matter how hard you concentrate on staying left, a life of driving in the US forces you to expect oncoming traffic from the other side. Thankfully, the captain transitions easily from the helm to steering wheel and we made our way around the island without incident. Our main objective was to provision aka get groceries aka find pineapple for the captain. The guidebooks told us there were three markets on this south side of the island. The books also said there was a giant hole on the way.

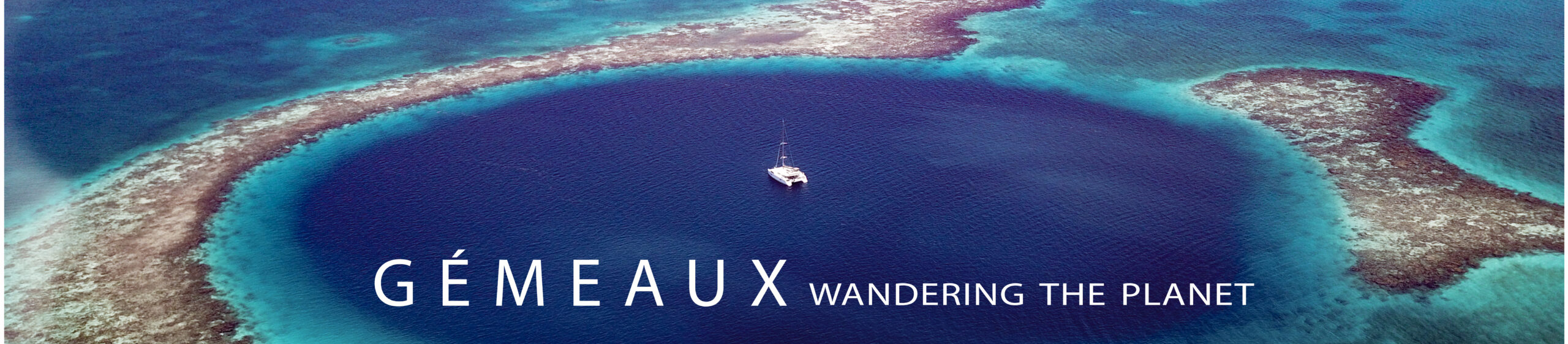

We’ve had the good fortune of visiting two blue holes on the planet, both from the decks of Gémeaux as she floated directly overtop the deep ocean chasms. Dean’s Blue Hole, however, was accessible from land and honestly, I had low expectations as we drove down a dirt road until it dead ended. I wasn’t even sure dragging along snorkeling equipment would be worthwhile, but as we walked around the corner I gasped at the unexpected splendor.  Nestled at the base of a natural rocky amphitheater with an entrance from a shallow lagoon stood an unspoiled circle of flat water that covered the shades of blue rivaling a box of Crayola crayons—baby blue to metallic seaweed to turquoise and finally to an inky blue as the sand funneled dramatically into the abyss. A platform was tethered in the middle where free divers gather each year in an international competition to determine who can dive the deepest. This spectacular sinkhole plunges 663 feet and the recordholder has seen half of it…in a single breath. We used several breaths to comfortably snorkel the perimeter—shallow and friendly on one side where you could inspect each pristine granule of sand, but a sharp drop into dark eerie oblivion on the other side. Allen dove down about eight feet and spotted a grouper as big as a car, trapped forever in this hole, having now outgrown the only exit route through a foot of water.

Nestled at the base of a natural rocky amphitheater with an entrance from a shallow lagoon stood an unspoiled circle of flat water that covered the shades of blue rivaling a box of Crayola crayons—baby blue to metallic seaweed to turquoise and finally to an inky blue as the sand funneled dramatically into the abyss. A platform was tethered in the middle where free divers gather each year in an international competition to determine who can dive the deepest. This spectacular sinkhole plunges 663 feet and the recordholder has seen half of it…in a single breath. We used several breaths to comfortably snorkel the perimeter—shallow and friendly on one side where you could inspect each pristine granule of sand, but a sharp drop into dark eerie oblivion on the other side. Allen dove down about eight feet and spotted a grouper as big as a car, trapped forever in this hole, having now outgrown the only exit route through a foot of water.

Like every good island shopper, we resumed our provisioning with salt on our skin and sand between our toes. Every few miles driving down the island’s only paved road, we would pass a different settlement, many named after the family who first settled the land and thereby creating the town name in the possessive form, which struck me as funny—Gray’s, Dunmore’s, Adderley’s, Gordon’s.

Each township was announced with a sign, followed by its own church and cemetery filled with names that matched the town sign minus the apostrophe. Rock walls, homes, and churches from plantations of an earlier era bordered the road, most overgrown by scrub but many remarkably intact. It was sad to this National Park Service brat to see these structures sit neglected— weather and brush erasing more of its history each year. A few settlements included newer buildings that could be distinguished only from this century by the laundry hanging outside or a hand-painted sign offering something for sale.

The allure of a local Farmer’s Market was too much to pass up so we made a detour from the main road. We recently had learned about the local style of pot-hole farming where fruits and vegetables are planted in limestone holes, the only place where good top soil accumulates on an island of hard dirt. We were told there was a pineapple farmer on the island and we could hardly wait to find crowns of pineapples growing randomly in nearby holes. Sadly, the only pineapple we found were embroidered on dish towels, as we discovered that a Bahamian Farmer’s Market sells more hand-made crafts than produce. We pressed on to market number one in Hamilton…er, Hamilton’s.

It’s worth mentioning at this point that Safeway and certainly Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods are a mere memory. We’re long past hoping to find radishes and spinach and milk that doesn’t expire tomorrow. We get excited when we spot celery and romaine hearts. We get super excited when we find them without any brown wilting leaves. We’re 200 miles from Nassau and another 150 miles from Miami—it takes a lot of ships and a very long time for produce to reach these little towns. Desperate for anything fresh, we hit the jackpot at the three

It’s worth mentioning at this point that Safeway and certainly Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods are a mere memory. We’re long past hoping to find radishes and spinach and milk that doesn’t expire tomorrow. We get excited when we spot celery and romaine hearts. We get super excited when we find them without any brown wilting leaves. We’re 200 miles from Nassau and another 150 miles from Miami—it takes a lot of ships and a very long time for produce to reach these little towns. Desperate for anything fresh, we hit the jackpot at the three markets and left with fruits and vegetables we would have thrown away in the US, including two spongey pineapple that we savored to the very end as we later visited islands lacking any store or apostrophe. Back at the marina, we carefully stowed our prized possessions and took full advantage of someone else’s quest for sustenance. We sat outside by ourselves on the restaurant balcony in a brisk, but Covid-safe breeze and enjoyed the simple pleasure of being served and a break from rationing vegetables.

markets and left with fruits and vegetables we would have thrown away in the US, including two spongey pineapple that we savored to the very end as we later visited islands lacking any store or apostrophe. Back at the marina, we carefully stowed our prized possessions and took full advantage of someone else’s quest for sustenance. We sat outside by ourselves on the restaurant balcony in a brisk, but Covid-safe breeze and enjoyed the simple pleasure of being served and a break from rationing vegetables.

Sated with a full refrigerator and a dose of civilization, we continued our pursuit of faraway islands. The south side of Long Island was the perfect jumping off point for the Bight of Acklins—a 500-square mile shallow lagoon that draws bone fishing enthusiasts, as well as those who just like to be off the grid. Water is so shallow you can practically walk across the Bight, making it difficult to navigate even for a catamaran with a 4-foot draft. We dropped anchor in what seemed miles away from land, yet in only a few feet of water that is normally only close to shore. During our three-day visit, we saw one local fishermen, four ospreys, and several barracuda who stalked us curiously (and too close for comfort) as though we were their first human sighting. The Acklins were remote above and below the water. Generally, this kind of isolation is paradise for us. However, high winds and a very strong current kept us confined to Gémeaux, unable to explore or even swim, for fear of being swept downstream to another island. Finally, on the last day when the weather settled, we dinghied to shore for a walk on a beach of floury sand and sailed close enough to Bird Rock Lighthouse, under new management by a pair of ospreys.

Long Island also is well-positioned for sailing to the southernmost chain of Bahamian islands—The Jumentos and The Raggeds, a favorite destination we discovered nearly a year ago when we began exploring The Bahamas northbound from the Caribbean. These rugged islands are a natural quarantine—their remote location isolating us from the dramatic change our planet has suffered over the past 12 months. As this crazy year draws to an end, we are grateful to have the opportunity to live safely in this beautiful place. Unsure of what the new year will bring, we are at least certain of our plan next week. We will return to Long Island since there is an entire west coast we haven’t yet explored. And…because we’re out of pineapple.

Enjoyed this post?

Sign up to receive email notifications of future posts!

Always love hearing about your adventures!

Wonderful!

Wishing you and yours peace and health in 2021. xo

thanks for sharing – always love your stories and love of nature/earth/sea.

Great post, as always! I hope you had a chance to try the pineapples that they grow on Eleuthera Island? They’re wonderful. There’s also an interesting history about Hawaii taking over the pineapple market and squeezing out the Bahamas. If Allen loves pineapple, then you’ll definitely need to go to the Azores! Some fab ones there too, and an interesting technique for getting them to grow there.

Hello Barb! Awesome information. We will definitely try Eleuthera pineapples…not sure we’ll make it to the Azores but that sure is a motivator!

Beautiful! We were at Ocean Isle, NC for several days to rendezvous with kids — not exactly the same beach experience!

Enjoy your beachtime! Hope you left your state in a good state so we have much to celebrate on Tuesday!